Climbing with an Alpenstock

~

“[The alpenstock] has a long tang running into the wood … and its termination is extremely sharp. With a point of this description steps can be made in ice almost as readily as with an axe.”

The first quote is from Mountaineering by C.T. Dent, published in 1892. The second is from Edward Whymper’s Scrambles Amongst the Alps (1871). By the closing years of the 19th century the alpenstock was rapidly fading from use: a relic of older times when mountaineering was a heroic business and specialist equipment did not exist.

In this article I’d like to discuss this humble item of climbing gear and hopefully go some way towards demonstrating its importance to the development of mountaineering as a sport.

What is an alpenstock?

Firstly, definitions! Nowadays the word “alpenstock” is used interchangeably with old-fashioned ice axes of the sort popular until the 1960s. Any ice axe with a shaft in excess of 75cm (especially one with a wooden shaft) is commonly called an alpenstock in the 21st century. However, this is factually incorrect.

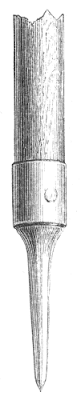

An alpenstock is a simple wooden staff, an inch or less in diameter, capped at one end with a steel spike. The length varies between 4’6″ and around 7′, depending on personal preference. That’s all there is to it!

Its function is primarily as a support or third leg to aid balance while climbing steep snow or crossing a glacier. The spike anchors the climber firmly to the mountain and can even be used to chip out steps in ice or hard snow.

“Alpenstock” is a German word; the French is baton, and English explorers often simply used “stick” or “fell pole” (although the German and French terms were also commonly used by Englishmen). “Alpenstock” was sometimes mistakenly pronounced “helping stick” by English tourists.

Some words from Edward Whymper on the subject of the alpenstock:

“When a man who is not a born mountaineer gets upon the side of a mountain … he ultimately procures an alpenstock and turns himself into a tripod. This simple implement is invaluable to the mountaineer, and when he is parted from it involuntarily (and who has not been?) he is inclined to say, just as one may remark of other friends, “You were only a stick—a poor stick—but you were a true friend, and I should like to be in your company again.”

When were they first used?

Alpenstocks are the oldest mountaineering tools known to mankind, first used by shepherds, travellers, and anyone else venturing into steep terrain. They were probably used by Neolithic people and were certainly used by the Romans. When Mont Blanc was first climbed in 1786, Balmat and Paccard were armed with alpenstocks and short hatchets–a combination that served mountaineers for over sixty years until the ice axe was invented in the 1850s. In the old days, the stick was used for balance and the hatchet was used to make steps where required.

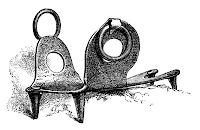

|

| Crampon – 1860s |

It’s worth highlighting the fact that crampons were commonly used in the Alps between the 1780s and the 1820s, but had fallen out of favour by the early 1840s and were not widely adopted again until the early 20th century. With spiked shoes, less emphasis was placed on cutting steps and therefore the hatchet was less frequently used. After crampons went out of fashion, climbers used hobnailed boots and were obliged to cut steps more often.

|

| An ice axe – not an alpenstock! |

The ice axe boasted greater utility in the form of a combined cutting blade and pick used to fashion steps in hard ice. It both enhanced and replaced the alpenstock. Although this process took time, by the early years of the 20th century the transition was almost complete.

|

| A modern alpenstock |

In the Alps, most of the glacier passes were first climbed by men wielding alpenstocks. Some surprisingly difficult mountains were also climbed in the pre ice axe era, for example the Jungfrau and Wetterhorn. This simple tool was of vital importance because it was cheap and ubiquitous, and added a modest degree of safety to the business of crossing glaciers and climbing mountains. It therefore helped propel Alpine exploration into a the limelight of popularity, and well into the 1860s it was perfectly normal to see mountaineers climbing major peaks the old-fashioned way, with stick and hatchet. Some climbers, for example Albert Smith, remained staunch opponents of the ice axe, claiming the traditional ways were better.

In Great Britain, the alpenstock enjoyed an extended spell of use. Ice axes were almost unknown in the Scottish mountains until well into the 1880s, although by the 1890s a growing emphasis on climbing (as opposed to mere hillwalking) led to the gradual adoption of the axe by British mountaineers.

In 2013, the ice axe is seen as an essential safety tool for all forms of winter mountaineering, and the alpenstock has been replaced by the telescopic trekking pole: a useful item for approaches and easy walks, but unsuitable for mountaineering.

An accident on the Matterhorn

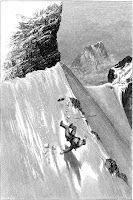

In 1862 young Edward Whymper was carrying out a determined campaign to be the first man to climb the Matterhorn, Forbes’ “impossible monolith” near Zermatt. In his classic work Scrambles Amongst the Alps we read this harrowing account of an accident that befell him while attempting to cross an icefield armed with nothing but an alpenstock and nailed boots:

|

“So I held to the rock with my right hand, and prodded at the snow with the point of my stick until a good step was made, and then, leaning round the angle, did the same for the other side. So far well, but in attempting to pass the corner (to the present moment I cannot tell how it happened) I slipped and fell. The knapsack brought my head down first, and I pitched into some rocks about a dozen feet below; they caught something and tumbled me off the edge, head over heels, into the gully; the bâton was dashed from my hands, and I whirled downwards in a series of bounds, each longer than the last; now over ice, now into rocks; striking my head four or five times, each time with increased force. Bâton, hat, and veil skimmed by and disappeared, and the crash of the rocks—which I had started—as they fell on to the glacier, told how narrow had been the escape from utter destruction. As it was, I fell nearly 200 feet in seven or eight bounds.”

What is it really like to climb with an alpenstock?

|

| The author armed with his alpenstock |

I own a short, lightweight alpenstock, constructed from a broom handle and steel spike. It’s just over four feet in length and the handle end is wrapped with rubber self-amalgamating tape to provide a sturdy grip (not quite a period detail, but a very practical one!) I also chose to add a tether made from a short length of rope.

Although most of my historical climbing escapades are accompanied by my trusty vintage ice axe, I’m currently writing fiction set in an earlier period so it’s only right that I should try out the older technique for myself! I’ve been on several outings with the alpenstock, although until now I have not found myself on hard snow or ice where stepcutting would normally be required.

Frankly, the idea of trying to chip steps with the point of an alpenstock isn’t a very appetising one, and I can appreciate why the pioneers readily turned to ice axes when they became widely available. However, for general hill use the alpenstock is a great bit of kit. It’s almost as light as a trekking pole. It doesn’t fold shut, of course, but that’s actually an advantage: what it loses in compactness it makes up for in rigidity, simplicity, and reliability.

I’m sufficiently comfortable using my alpenstock that I would be very happy using it on mountaineering ascents throughout the year in Scotland, but only on easy terrain and only if I have crampons with me. Of one thing I can be completely certain: for as long as mankind feels the need or inclination to climb mountains, some form of spiked staff will exist as an aid to balance.

Related posts

Oscar Eckenstein: the first true innovator of climbing equipment?

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)