Going paperless in the hills – how feasible is it?

In 2016, is it yet feasible to leave the paper maps at home when you go into the mountains? After a recent hardware failure, I don’t think we’re quite there yet.

Paperless. It’s been the dream for decades, hasn’t it? At home, and in the office, computers promised to free us from the reams of paper that once held us prisoner. In some professions (for example, mine), that promise has been largely fulfilled; it’s actually quite rare that I have to print anything off these days, and the vast majority of my work is handled digitally.

But what about when we go into the mountains?

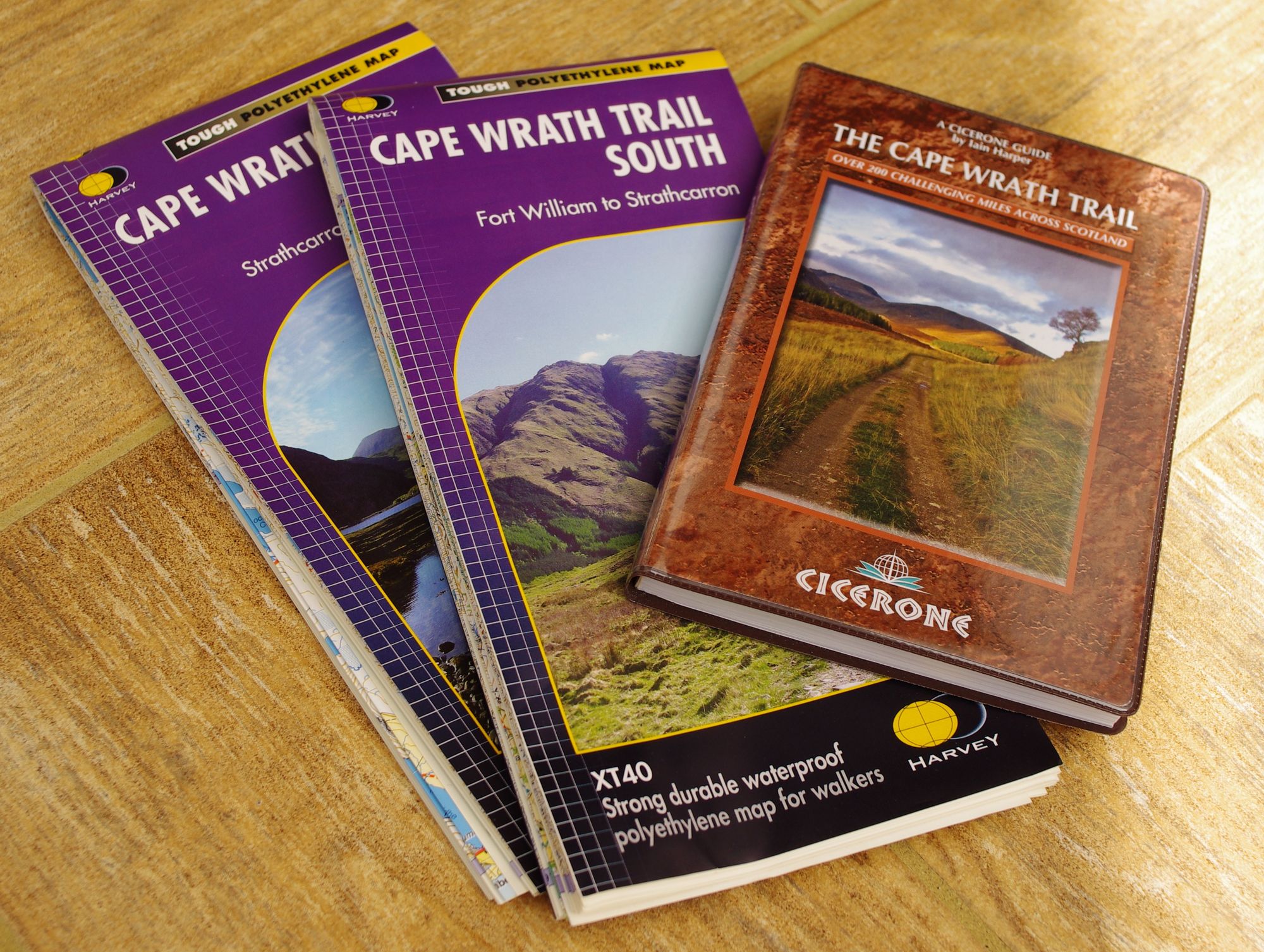

The traditional way

For decades, hillwalkers and backpackers have adhered to a simple maxim: always carry a map and compass into the mountains, and know how to use them. Map and compass form a simple and reliable system for navigating in the outdoors. There is a learning curve, but it isn’t too steep, and once mastered the skills last a lifetime (so long as you don’t get too rusty!). Reliability is of course not perfect: maps can be blown away or destroyed by water, compasses can break or be confused by magnetic rocks. Tiredness or a lapse in concentration can lead to navigational errors.

Although map and compass is not a foolproof or infallible system, it is arguably the simplest and most reliable way of navigating in the outdoors. Nowadays there are other options which can supplement this basic setup.

GPS arrives

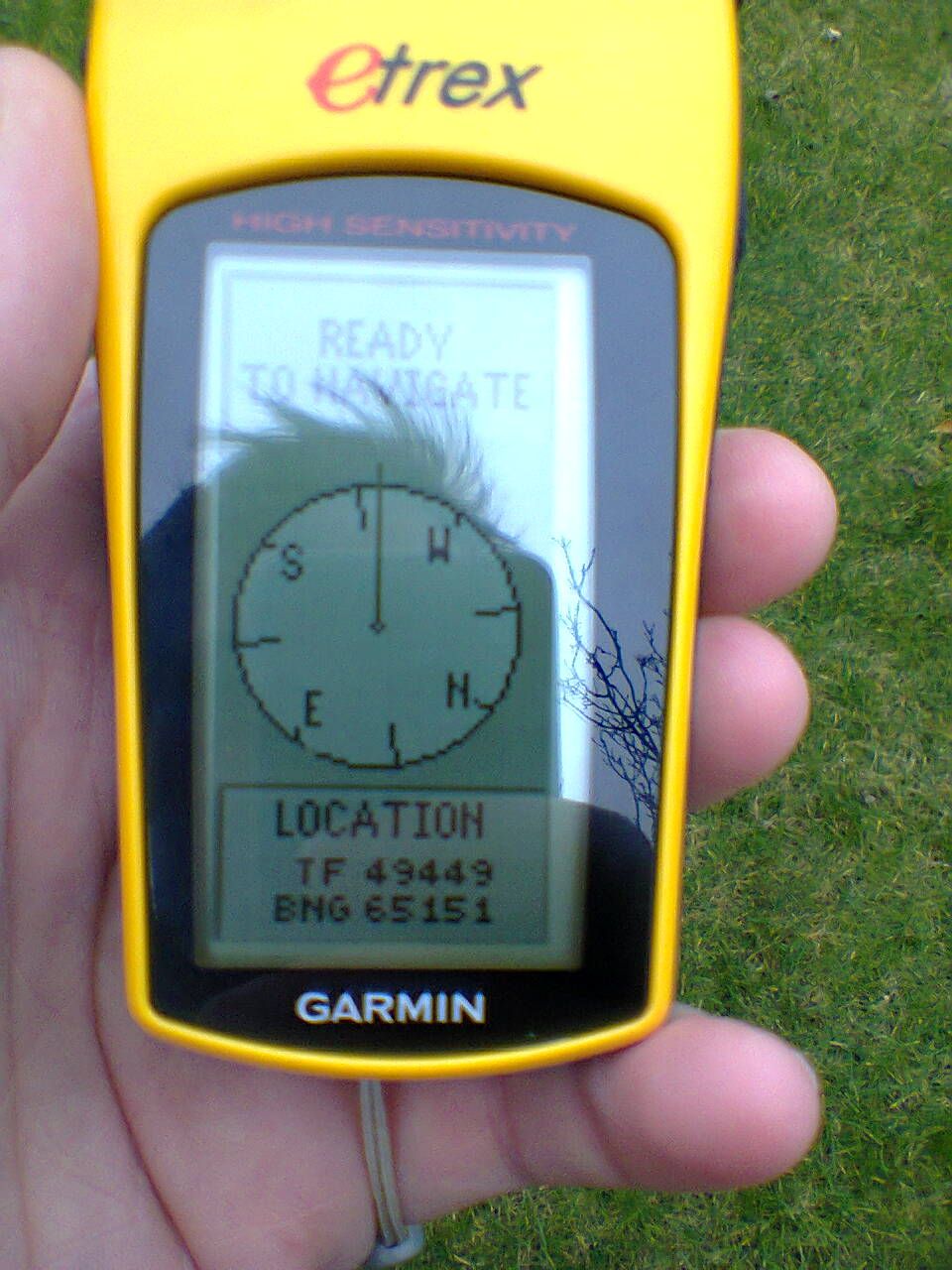

Over the last twenty years, digital methods of navigation have begun to make their mark on hillwalking and backpacking. At first the options were limited to simple GPS units. In the 1990s my dad had a Garmin 12XL – a bulky machine capable of producing an OS grid reference, marking waypoints, and navigating in straight lines between stored locations. It was really designed for marine use, but we found it very useful as a supplementary navigation aid when out walking.

In the early 2000s, I bought a Garmin eTrex. This is essentially an updated and easier-to-use version of the 12XL, and I used it for many years. It was my constant companion in the hills, tracking where I’d been, maybe producing a grid reference if I needed to be sure exactly where I was, and occasionally offering some fine-tuning to my navigation. It was very much a supplementary tool and was useless without a good map and baseplate compass, but it occupied a valuable niche (and, indeed, it still works perfectly).

In about the same period, GPS units with built-in maps started to appear on the market. I have never used one of these machines, but I remember the outcry they caused at the time – what if people try to navigate with a GPS alone, and no map as a backup? The idea struck me as dubious. Battery life in GPS units was never that great in the early 2000s, and electrical or mechanical failure was always a risk.

But tech marches on at a bewildering rate, and now, in 2016, most hill-goers will carry a smartphone on their travels. 1

The smartphone navigator

Smartphones are suitable devices for navigation both on and off the hills. Modern devices have precise and fast GPS capabilities, long-lasting batteries, and the ability to easily load a vast array of supplementary software – some of which is specifically tailored for mountain use. A smartphone off the shelf is useless in the hills, but with the addition of the correct app (Viewranger, Memory Map, or OS MapFinder) and the purchase of some map tiles it becomes a robust system for mountain navigation.2

I’ve been a Viewranger user for some years now, and although there are times when I have wondered if it’s dulling my traditional map-and-compass skills, I’ve come round to the idea that the convenience factor is huge. For simple navigation where no bearings have to be taken – which accounts for over 90% of navigational tasks – I’ve found that turning to Viewranger can actually be much faster than opening up the map, and over the course of a day’s walking these time savings are pretty significant.

So, there are advantages in using a smartphone in addition to map and compass, which (few would deny) are still vital bits of kit in the rucksack of the modern adventurer.

Or are they?

The smartphone-only proposition

Last year, when I started taking a hard look at my rucksack contents and thinking about how I could cut down on weight, the idea crossed my mind that in certain circumstances it might be feasible to go paperless in the hills – to navigate with Viewranger alone, and not to take any paper maps at all.

Traditional thinking would call this idiotic, but then again many ‘rules’ are being broken with modern approaches to equipment and technique. Stout boots were considered essential for many years too, and to wear trainers in the hills was seen as an invitation for a Mountain Rescue callout – yet now many of us wouldn’t think twice about venturing into the most difficult mountain terrain clad in trail shoes. Things are changing fast, and I know of several long-distance hikers who do all their navigating on a smartphone now, even in remote and challenging areas. So it’s possible, but is it wise?

I have tested the waters gradually. It’s now quite normal for me to go out walking in the Lincolnshire Wolds without a paper map; after all, what’s the worst that can happen in countryside where you’re never more than a mile or so away from a road or a village? In well over a year of relying on smartphone + Viewranger for lowland walks, nothing has gone wrong and at no point have I wished I had a map and compass.

When it comes to venturing into the mountains, I’ve been much more cautious and have not, to date, dared go entirely paperless. But I have on several occasions left the analogue gear in my rucksack and navigated by Viewranger alone. In fact, on both of my shorter backpacking routes last year (the Settle circular route and the tour of Kinder Scout) I did not use paper mapping or a compass, beyond carrying them as a backup.

The biggest test of the digital approach came in September 2015 when I hiked the Tour of Monte Rosa – again, entirely with digital mapping. The paper maps, and my compass, remained as vestigial backups in my bag, and that’s when I started to wonder if the traditional methods had become, for me, yet another symptom of ‘packing my fears‘.

I wouldn’t take a spare stove with me just in case the first one failed, so why was I being so cautious with navigation? I soon realised that things are a little more complicated than that – and a recent incident convinced me that going entirely paperless is not a good idea.

The case against going paperless

The thing is, for serious or remote trips, navigation is absolutely vital. If your stove breaks down, you might have to cold-soak your meals for a few days, but it’s hardly life-threatening. If your navigation system breaks down, you could end up in the wrong valley and add days until your next resupply, risking some serious hunger. Or you could navigate over a cliff.

The KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid) rule is worth adhering to when it comes to backpacking equipment. The more complex an item is, the more likely it is to go wrong and the less easy it is to fix.3 Many items of backpacking equipment are not easily field-serviceable, but I’d hazard a guess that if your smartphone decides to crash and erase its memory then you won’t have the tools (or expertise) to fix it in the wild.

I learned this lesson the hard way on my recent trip to the Ben Alder Munros. For years, I’ve carried a 12,000 mAh power bank which is used to supply energy for everything electronic I take on the trail. It has given me excellent service since about 2011. However, on this trip it failed without warning.

I was getting ready to turn in for the night after arriving on the train. My phone, which I’d been using to listen to audiobooks on the journey up, was at about 50% battery capacity, so I plugged it into the power bank and pressed the ‘on’ button. The lights blinked and went out; I had expected them to glow steadily, indicating the device was supplying power. I tried again. Same result. The thing was dead. I’ve since had to replace it with a newer model.4

Realising I had no external power source, I immediately powered down my phone to conserve the final 50% of battery life (in case I needed to use it as an actual phone). This meant, of course, that I was unable to use Viewranger and had to navigate the old-fashioned way, with map and compass.

Fortunately this was not a problem as I had the equipment and my navigational skills are up to date. But if I had (foolishly?) decided not to take these items then things would have been altogether different. Would 50% of a Moto G3’s battery have been enough to see me through the whole trip? Maybe, but batteries can be affected by cold temperatures in unpredictable ways. I would probably have had to cut the trip short.

This served as a valuable and timely lesson. Planning for the Arctic Trail later this year is underway, and I must admit I had – briefly – considered the option of going paperless. But the idea of a critical electronic device failing unexpectedly, perhaps days from the nearest road, does not fill me with confidence.

A paper map can blow away or be pulped by rain, but it doesn’t suffer from malware, it won’t crash, and it is not powered by fragile and mysterious chemical power plants. In short, map and compass adhere to the KISS principle: provided you don’t damage or lose these items, they’ll probably do their job just fine.

Don’t get me wrong – a smartphone is very useful for backpacking, and I will continue to use mine as a navigational tool in conjunction with my traditional skills. But (with the exception of lowland walking) I won’t make the step to paperless for navigation, because the potential consequences of a hardware or software failure are simply too severe to risk. Leaving paper maps at home would be a good example of ‘stupid light‘, I think.

- I wrote this article, Electronics on the Trail, late last year. It illustrates my current approach to the use of various items of gadgetry in the hills. ↩

- As I mention in my article linked in footnote 1, there are important precautions to take in order to make your phone ‘hill-ready’. Waterproofing, protection from drops, power conservation, and supplementary power supply are the main ones. ↩

- This is also why I favour a closed-cell foam roll mat instead of an inflatable sleeping pad these days. I’m also wary of complicated stoves such as Jetboils. ↩

- Here’s the unit I purchased to replace it. ↩

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)