Twenty years as a writer: a first look at The Farthest Shore

A few thoughts about the long and winding road to the publication of my new book.

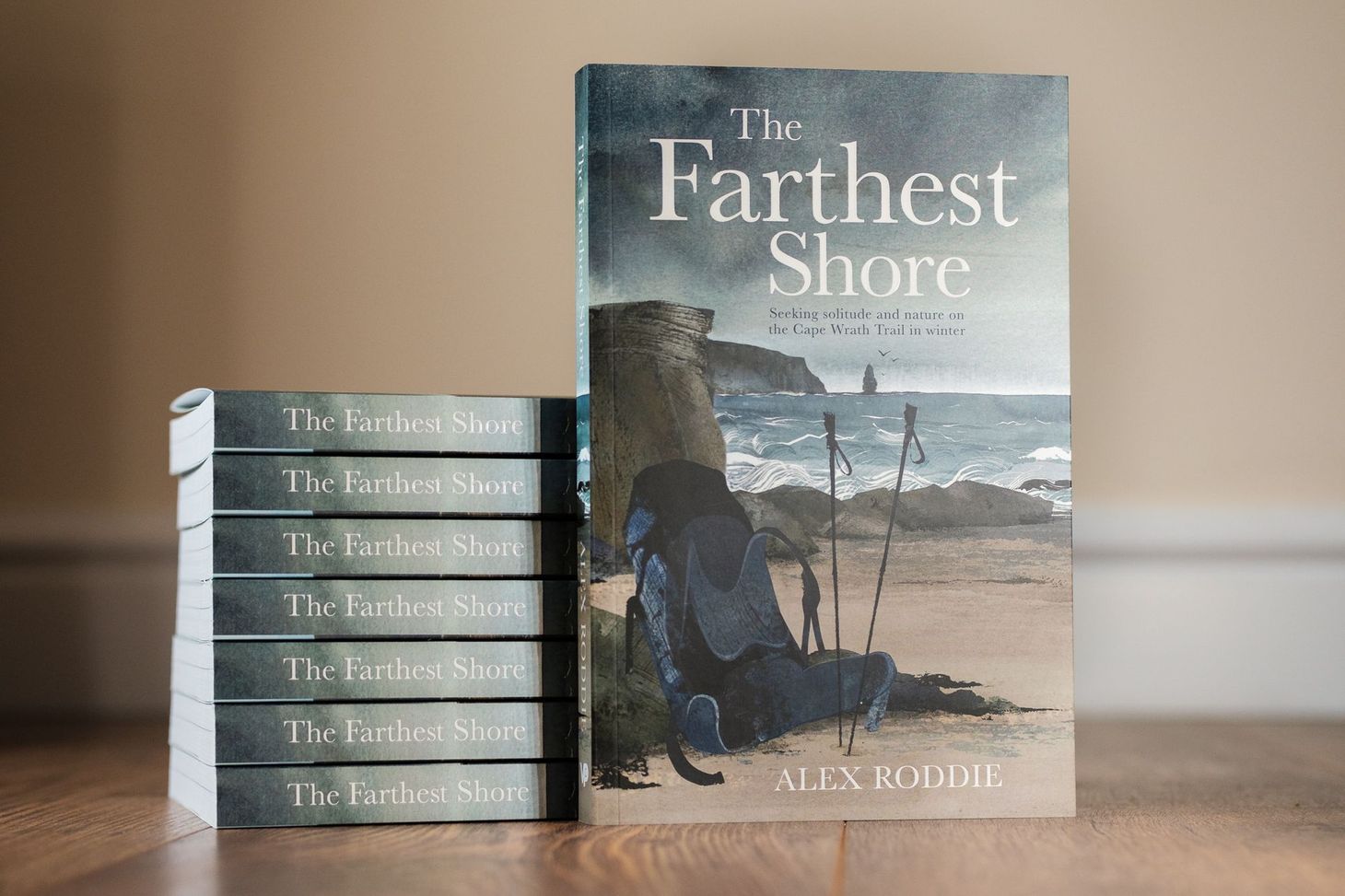

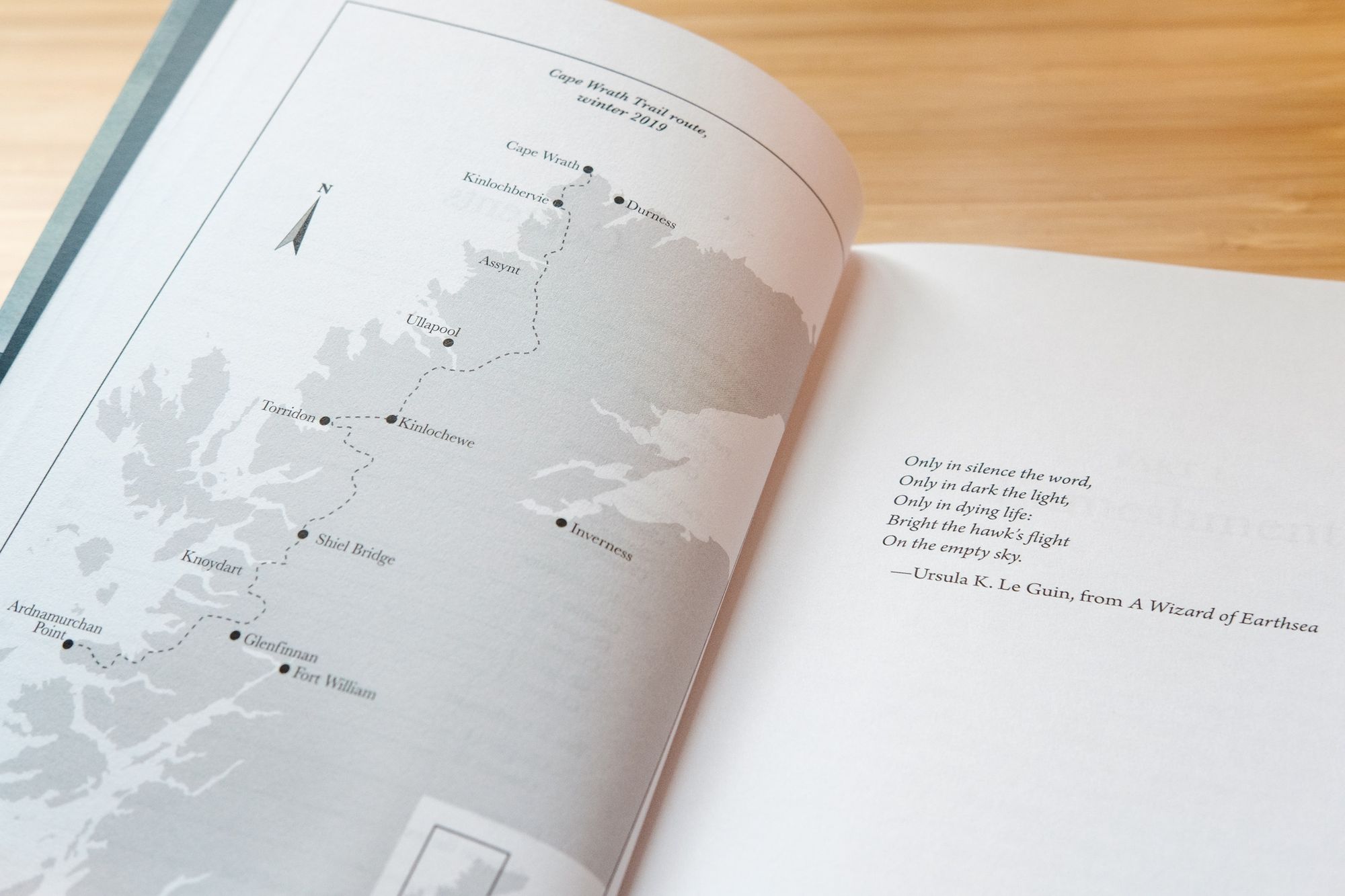

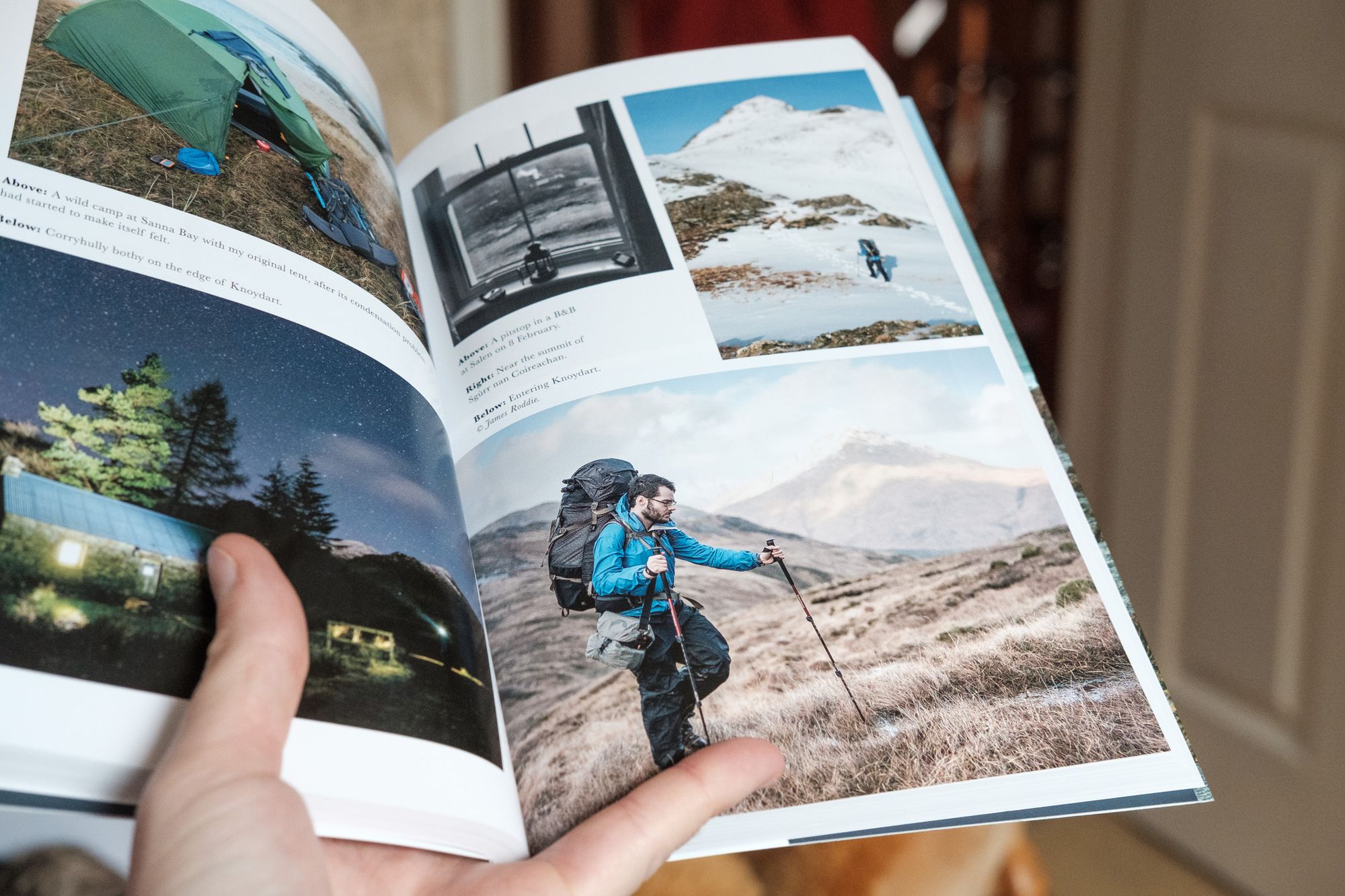

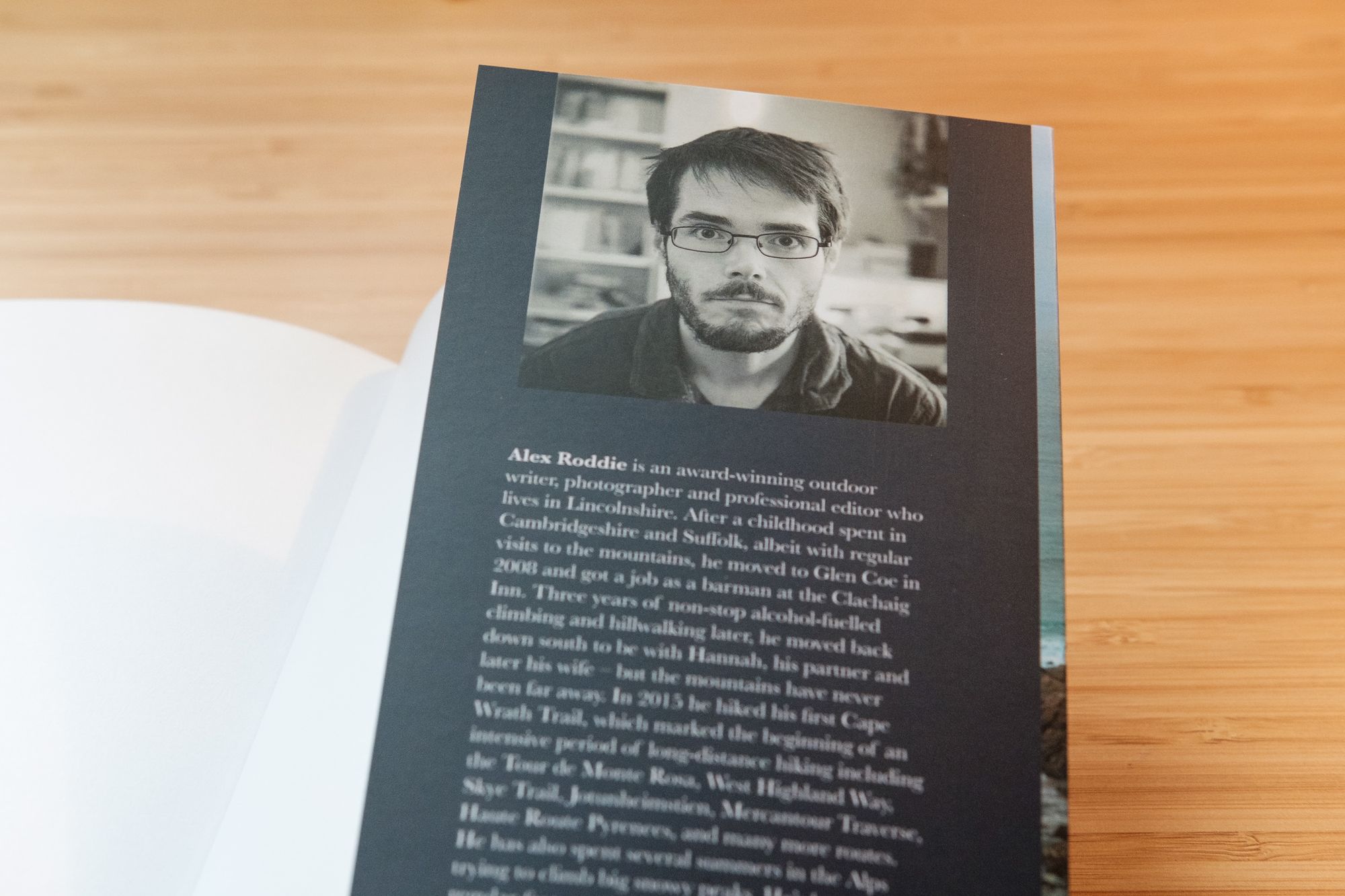

This week, I took the train to Sheffield and paid a visit to Vertebrate Publishing, where I supplied cake and sat down for a few hours with a single task: to sign several hundred copies of my new book The Farthest Shore. I took my own author copies back home with me. Here are a few images of the finished article – and a few thoughts about how I got here.

This is my second traditionally published book, my fifth published book overall, and probably something like the fifteenth or sixteenth written (honestly I lost track years ago), but in many ways it feels like the first.

After so long dreaming, thinking, writing and of course walking, it feels good to see the book in its final form. And it looks fantastic – the editorial, design and production teams at Vertebrate have done a genuinely wonderful job. Right from the start of this process, when I popped by the Vertebrate office to chat about my idea with Jon Barton in late 2019, I have felt in safe hands. Vertebrate are of course a commercial operation. An idea has to be commercial enough to sell, but at no point did I feel that I was being asked to make unacceptable artistic compromises in order to make a more commercial product. Partly I think that’s because I know how the publishing industry works and was quite happy to be flexible where needed. However, Vertebrate also treat the artistic visions of their writers with respect. I was frequently consulted throughout the process on everything from page layout to cover design, and my input was taken on board. The final result is a book that I’m proud to put my name to.

I take the time to mention this because one concern that writers sometimes have with traditional publishing is that their wishes might be ignored, steamrollered by the crass demands of commerce. This is one benefit of self-publishing: you have the freedom to do anything you want (although you have to accept the consequences of that too). Of course, all publishers are different – and if your ideas are rubbish then a steering hand can be valuable.

Early in this journey, almost twenty years ago, I remember reading a piece of advice that stuck in my head: ‘If you think that your writing has been dictated to you by God then only you and God are going to read it.’ In other words, no idea is too precious to be improved, and no writing is too precious to be edited. But there’s a balance to be struck too. The path to finding your voice is different for us all.

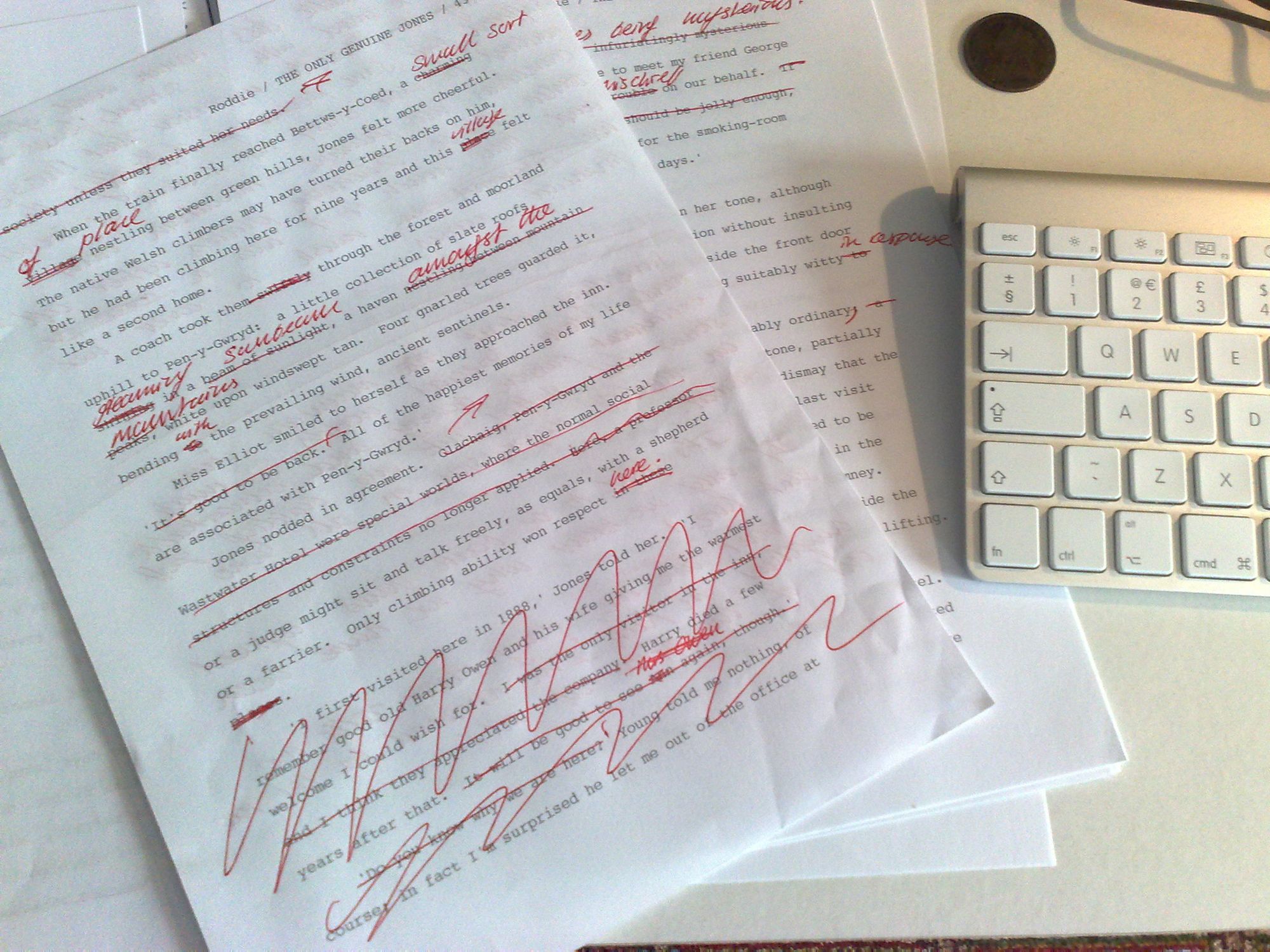

I’ve been looking through old photos lately and feeling a bit nostalgic. In August 2011, I was deep in the red-pen edits of The Only Genuine Jones, the mountaineering novel that would eventually become my first self-published book1. This was a breakthrough time for me. I’d been writing fiction for about a decade already; I began writing my very first novel manuscript, an awful and derivative fantasy tome called The Chronicles, in about 2001 at the age of fifteen. For ten years I had been working on my style and voice, writing books that would never be published because I believed in the apprenticeship process, in honing my craft in private before showing my mistakes in public. Before I sought publication, I wanted to be a Good Writer.

Of course, the tools for self-publishing simply didn’t exist in the first few years of the 21st century. Things were changing though and by 2011 I felt ready. The tools finally existed to easily self-publish both electronically and via print on demand. The Only Genuine Jones was my statement to the world that I was done with the apprenticeship – that I was ready for my work to be read. The result was modest success. The book sold reasonably well for a couple of years and made a decent-ish profit, and the two books that followed, Crowley’s Rival and The Atholl Expedition, had their fans too2. However, as I began to grow as a non-fiction writer, I increasingly saw the flaws in my mountaineering fiction. I started to realise that maybe I’d been premature in putting those books out there after all. Yes, self-publishing means that anyone can publish anything, and that is an empowering thing, but despite my years of development I think it emboldened me to publish before I knew what I really wanted to say.

The truth – and this is a truth I’d failed to grasp ten years ago, puffed up by the idea that I had served my apprenticeship and deserved to be considered a Good Writer – is that the learning process never ends. I know that I am a better writer now than I was ten years ago, and ten years before that. In another ten years I may look back at my work from the early 2020s as clumsy and naive. Cleave to that philosophy too literally, though, and you’ll never publish anything. More important is the fact that I was still flailing around for my voice in 2011, and opportunity had made me blind to my own shortcomings. I could have benefited from a gatekeeper or two giving me some harsh truths3.

I’m not saying that The Farthest Shore is a literary masterpiece, or that I’m going to sit back and wait for the book prizes to start rolling in. Nobody ever ‘arrives’ because there is always another staircase to climb. Truthfully, I’m more full of doubts about this book than about anything else I’ve written. I know that I’m happy with it as an expression of my own soul and my own experience, and perhaps that should be enough for any writer, but I’m also aware that I’m still a young man and have much to learn. The more experienced a writer I become, the more I realise that the road ahead of me is long.

Where am I driving with this? Am I telling writers to forget about self-publishing that first book, hit pause on their dreams for a decade while they build up experience? Certainly not – I think it’s fantastic that writers have so many options and tools these days. For some, publishing early and often is the right choice. You don’t have to get your work past the gatekeepers if that is not the best road for you. It’s easy, too, for me to look back on the path I have travelled and retrospectively say it’s the best one, blind perhaps to the hidden forks along the way.

What I have learned is this: finding your voice, and taking the time to work out what you truly have to say, are the important things. My path to get here has taken two decades, and stretches out ahead of me; for you the path may be very different, but it is a path worth treading no matter how long it may seem.

The Farthest Shore comes out on 2 September 2021, and is available to order now from Vertebrate Publishing.

- You can’t buy this book online any more, because I pulled all my early work from Amazon a few years ago, although there are always a few copies kicking around on eBay and in second-hand bookshops.↩︎

- Crowley’s Rival was always my personal favourite of the three. It’s a much stronger story and far more rooted in historical fact.↩︎

- Not too harsh, though, because writers are easily discouraged and confidence is fragile. It’s very important to give constructive criticism delicately to a writer who has poured their soul into a manuscript.↩︎

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)