A bit of bother on Barf – or, when smartphone mountain navigation gets complicated

Concerns raised over crowdsourced maps used by popular hiking apps – my input into a TGO report on the issue.

Carey Davies, editor of The Great Outdoors magazine, has just published a new report about mountain rescues in the Lake District connected to a dicey descent from a hill called Barf (yes, Barf). Specifically, it's about how this route is portrayed in the underlying OpenStreetMap data used by many popular hiking apps. I'd encourage you to read the report in full. It includes a number of quotes from me, plus some very interesting comments from an OSM representative (and the expected bland and pointless remarks from the Ordnance Survey).

Carey asked me to look into the issue because he knows I'm TGO's resident tech geek. I ended up sending him a bit of an essay of an email, and I thought it might interest my readers to post the full thing here, as it contains a number of bits and pieces that weren't quoted in the full article. Here it is in its original unedited state (I dashed it off in a bit of a hurry).

Any form of navigation is only as good as the underlying map data. More and more hillwalkers have turned to digital navigation software running on their phones – either as a backup to map and compass or, perhaps more commonly these days, as their main 'glanceable' form of nav. But although the merits of the apps themselves are often discussed, the data powering these apps comes under far less scrutiny.

Commonly used apps such as OS Maps, Outdooractive, Fatmap, and AllTrails give users a choice of which maps to use, but 'premium' topo maps often cost the user money. The free map layer is usually based on OpenStreetMap (OSM) data. It's free because it's open source, maintained by volunteers, just like Wikipedia. But more detailed map data such as the traditional Ordnance Survey 1:25,000 or 1:50,000 mapping is expensive, which is why it's rarely to be found in free apps. Although OSM data is quite comprehensive these days, and includes a wealth of information including contours, summits, streams, paths etc, it still isn't anywhere near as detailed, accurate, or curated as the likes of traditional OS mapping. Partly that's because nobody is being paid to do it; partly it's because volunteers sometimes get things wrong, despite good intentions. And partly it's due to the visual design.

Although OSM is moderated, just like Wikipedia, anyone can add or edit paths in the OSM data set, and these edits will then filter through to every app that uses the underlying data. For example, in my local area some of the public rights of way were missing from MapOut, my favourite OSM-based mapping app. I went to OpenStreetMap.org and added the paths manually. Voila, a few weeks later my added trail was in MapOut – and every other app I use.

This is a double-edged sword. Great as traditional OS mapping is, it isn't perfect, and paths evolve more frequently than OS maps get updated. This means that in some mountain areas there are paths missing from your standard Landranger or Explorer maps. OSM-based apps have many trails that users have added themselves. I've found this particularly useful in European countries where the official maps are either out of date or otherwise not very good, such as Italy – OSM is often better. Sometimes even in the UK it's useful to compare the OSM and OS maps to reveal routes that you might not have known were there. These can include vague but followable paths such as old stalker's trails. It's a useful additional resource.

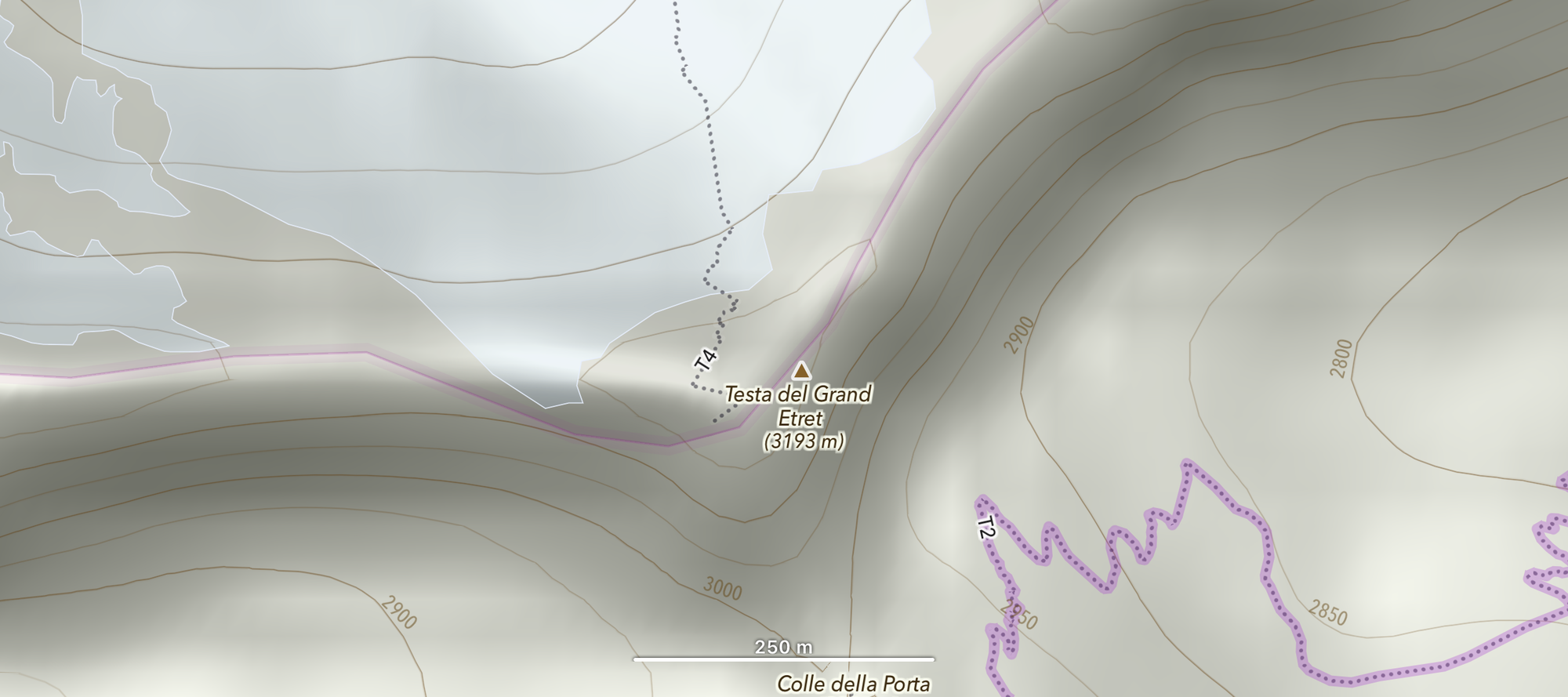

However, there is no quick and easy way to tell how difficult a user-added trail is. Most apps render them as simple dotted or dashed lines – even technical scrambling routes have little or no differentiation. In the Alps, some apps will show a T grade on the route if you zoom in far enough. For example, T3: 'Challenging mountain hiking. A footpath is usually available. Exposed places mostly secured with ropes or chains.' T4 and T5 include difficult scrambling, potentially up to Grade 3 or beyond. However, not every app includes this information (and it isn't obvious even when present). Some apps use more obscure terminology such as 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, which may or may not mean anything to the user (and this text is often tiny, only visible when zoomed a long way in, and there often isn't a map key).

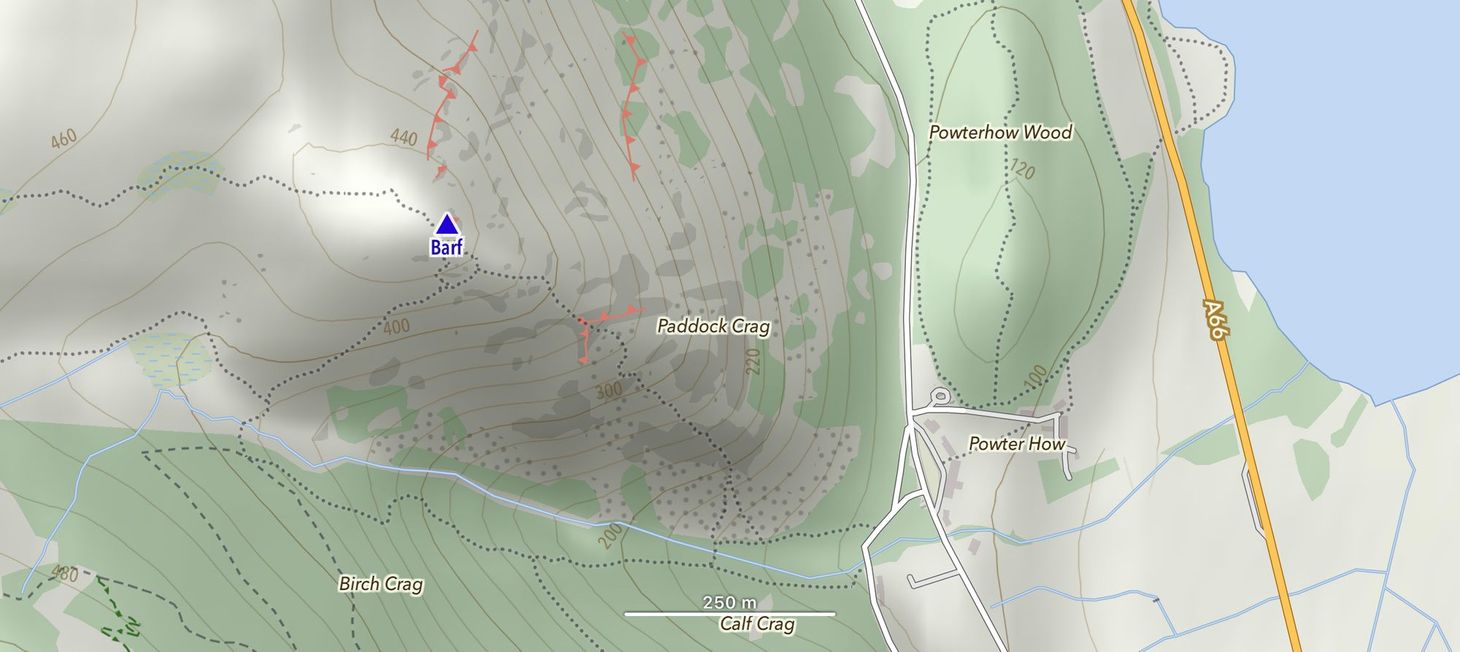

The problem arises when paths on the OSM data set are either inaccurate or just plain wrong – or when the user misinterprets the information. Recently, Keswick Mountain Rescue attended two callouts linked to the OSM-based hiking app AllTrails. In one, a benighted walker had attempted a shortcut shown on the map and got lost in the dark; in the other, a walker following a route on the app found it far more difficult than expected and became cragfast. In both cases the trail was clearly marked in the OSM data, but the difficulty (or visibility on the ground) was hard to tell from the app. In both cases no trail was marked on the traditional OS mapping – but, confusingly, the trail in question was also visible in the free basic map on the OS Maps app (which uses OSM data).

I have checked, and the same trail is visible on all the OSM-based apps I use. In the case of the descent from Barf, komoot does better here than most of the other apps: a dashed line becomes a dotted line where it passes over a crag. However, there is still no indication that this is an actual scramble rather than a walk.

Although media sources have been quick to blame reliance on smartphone apps as the cause of these incidents, the apps themselves are not to blame here – the problem is the underlying quality of the data, and the implied trustworthiness of it. When you follow a walk on AllTrails, Outdooractive, or komoot, it's presented as something you can follow safely, and there is no obvious reason to doubt it. In everyday life, we are used to apps being reliable and rarely have cause to doubt what we're seeing. It's rare, for example, that Google Maps shows a street that isn't there, but mapping a mountain isn't the same as mapping a city, and I don't think it's widely enough known that many of these apps rely on voluntary mapping contributions.

When I'm planning routes, I often use a mixture of different mapping sources, and cross-reference them against each other to come up with the optimum route choice. If the same trail is visible in OSM and my paper OS maps, it's usually solid. If, however, it's only available in OSM, and looks like an obvious GPS trace when you zoom in far enough (with 'spikes', indicating a GPX file uploaded straight from a watch, phone, or GPS), then I'm much more wary. The problem is that not all users are even aware that this is good practice. And the apps don't tell you about these risks, so why would they?

Rather than blaming users for navigating with smartphones in the hills (which, let's be honest, even the most experienced of us do all the time now), I would like to see more visual differentiation between routes of varying steepness and difficulty. I'd also like to see more robust curation and moderation when new routes are added. However, this is an issue at the source – the OSM project – and the apps themselves have little control over this. The developers could, however, offer some form of onboarding or tutorial that helps users to make informed decisions about route choice using their software. Apps that maintain user-contributed route libraries, such as AllTrails, can certainly be more thorough with moderation too.

My opinion is that mountain walkers should not simply follow the arrow on an app – there are different ways to use these platforms. Use apps to help plan routes, and as a convenience on the hill, but I would argue that a basic grounding in navigation (regardless of the tech used) and using your own judgement rather than relying on an app to guide you is always what we should be aiming for. The important thing is to be in control of navigation, even if you're using an app.

One thing I didn't know when I emailed all this to Carey is that OSM already have a system in place for applying T grades to hiking routes – I had assumed that any such efforts were haphazard or piecemeal, probably at the whim of local volunteers. OSM clearly know about these problems and are trying to work on solving them. I hope that this article leads to greater collaboration between OSM, app developers, the hiking community, and ideally mountain rescue organisations. I now believe that this is more an app-design issue and less an issue with the underlying OSM data. The real takeaway here? This is a complicated issue with multiple factors at play.

I continue to be grateful that TGO provides such an intelligent and nuanced platform for discussing modern mountain navigation. For years, the magazine has helped me to campaign for safe digital navigation – not simply repeating the increasingly out of touch 'never use a smartphone to navigate in the hills!' advice we still hear from some quarters. However, powerful tools require skill and experience to use safely. And complex tools that have a web of dependencies are not always as predictable as simple tools that can be easily understood. Map and compass are certainly not going anywhere yet; they will continue to have an important place in the hillwalker's toolbox for many years to come.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)