Electronics on the trail – what works for me

Please note that this article is now out of date. Here’s an updated version.

“Nothing that uses a battery can be relied upon in the wild.” This is something we hear from time to time, but how true is it? What level of electronic gadgetry is necessary or appropriate in the outdoors? The purpose of this article is not to dictate what you should or shouldn’t do – it’s simply to demonstrate what works for me at this point in time, and to share some of the points I’ve learned over the years.

Read through the archives on this site and you’ll see that my attitude towards electronics on the hill has changed substantially several times. Sometimes I’ve been happy to take and use a smartphone; at other times, usually when I’ve been feeling too ‘connected’ in my everyday life, I’ve written about how I felt leaving the smartphone at home helped me enjoy the mountains more. I have experimented with carrying nothing but a basic Nokia dumbphone and a film camera with me. At other times I have carried far more tech into the wild.

The key lesson I’ve learned through all this is that there is no inherent virtue in being tech-free when you go into the outdoors. It’s up to the individual to decide what they need. If you go to the mountains to leave the Web behind, then by all means switch your phone off until you need it. Likewise, there’s nothing wrong with logging on if you happen to find some 3G signal. It’s easy to preach about the value of being disconnected in the outdoors until you’re on a long-distance hike and every moment of contact with the outside world is precious.

I’ll start this article by looking at the most versatile electronic device any hiker or mountaineer could ever use: a smartphone.

The smartphone

The model of phone you pick does not matter. Any smartphone you can buy nowadays will do the job handsomely

Smartphones haven’t been around for very long but already they have earned a place in the lives of many people. For the weight-conscious backpacker, a smartphone’s utility should be immediately obvious: it has the magical ability to replace numerous other items, if you let it and if you’re happy with the compromises involved.

A smartphone can replace:

- A traditional mobile phone

- A camera

- Most of the functions of a Web-connected computer, if you need such functions

- An MP3 player

- A paperback book or dedicated Kindle reader

- A paper notebook

- A mapping GPS (but not a paper map and compass)

- A barometer (generally only certain newer models)

- A watch (although I always wear a basic digital watch as well, as checking the time on a phone screen wastes power unnecessarily)

Of course, you may not carry all or any of these things anyway. But a smartphone gives you these functions without adding any weight whatseover, only power supply demands, and it’s fair to say that the majority of outdoor enthusiasts will have a mobile phone of some description for emergency purposes. Having experimented with going back to a basic phone for several reasons, I can confidently say there is no advantage in using a traditional non-smart phone. With careful power management – which I’ll come to shortly – a modern smartphone is simply a better choice due to its extraordinary versatility. And despite popular myths to the contrary, power reserve can actually be better than the Nokia bricks we remember from previous years.

The key is how you use it. Unrestrained use of a smartphone in the wild can only result in frustration and a drained battery, as I have discovered before. Many people will choose to keep it switched off unless they need to use it; my preferred strategy is to leave my iPhone set to airplane mode, which disables all wireless antennas. This enables me to use the device as a GPS. My software of choice is Viewranger, which works perfectly well offline. There is often no signal in the mountains, which discourages the pattern of frequent smartphone use you might be accustomed to in your regular existence – and besides, you will be busy hiking and enjoying the outdoors! Used in this way, an iPhone can easily last a fortnight between charges, which should be long enough for anyone.

The model of phone you pick does not matter. Some devices are better than others in terms of speed or battery life, and some are best avoided due to substandard software (Windows Phone, I’m looking at you), but generally speaking any smartphone you can buy nowadays will do the job handsomely. Some are even waterproof.

I prefer to use an iPhone due to excellent battery life, camera quality, and reliability. But it really doesn’t matter.

You don’t need many smartphone accessories in the wild. The only essential item is a good case – preferably a shock-resistant one. I favour the Griffin Survivor Core, which provides lightweight protection but does get very scratched (not a huge concern in the wild, I’d argue). Waterproof cases exist but these tend to be cumbersome and expensive. My solution to keep water out is simply to put the whole setup in a ziplock bag. This worked for the entire length of the Cape Wrath Trail despite almost continuous wet weather.

You may want to carry headphones for listening to music or audiobooks. The set that came with your phone is probably good enough – the lighter the better.

Lighting

This is the only truly critical electronic item for the wilderness traveller. Most of us will choose to carry a headtorch. There are many models to choose from, some optimised for sheer power, others for weight. For summer backpacking, the only choice for me is the Petzl E+lite. This is an incredibly light headtorch at only 27g, and it provides enough light for use around camp or in a bothy. It isn’t really powerful enough for walking with, but for the majority of summer use that’s an edge case.

If I need more power – for winter trips, or summer alpine routes where pre-dawn starts are required – then I favour the Petzl Tikka XP2. This is still a lightweight device, but it produces an order of magnitude more light and a controllable beam. The small red LED is incredibly power efficient for general use in your tent after dark. Many headtorches require separate batteries, so of course it’s always wise to carry a spare set. Some models can now be recharged, which – if you’re carrying a portable power plant, as I recommend – makes things easier.

Camera

If you’re already carrying a smartphone, do you need a dedicated camera? I think that depends on what you want from your photography. If you are just looking to capture snaps for personal enjoyment, then the camera on a device such as the iPhone 6 or Galaxy S6 will be more than good enough for you. You can even print out images from these cameras at large sizes with little noticeable drop in quality, and of course they’re good enough for Web or blog use. Many ultralight hikers would not even consider carrying a dedicated camera in addition to their smartphone.

But if you want photos of publishable standard, of if you’re a photography enthusiast who wants more control over your photos, then a dedicated camera really is the way to go. The choice is, do you need a DSLR or will a compact camera do the job?

For years I carried cheap and nasty digital compact cameras into the mountains. They never worked particularly well and I broke or lost them at an alarming rate, most notably in 2008 when I got through three in one year. They offered no controls over the exposure and were in every respect worse than modern smartphone cameras.

In 2014 I got back into film photography after a very long hiatus. The best camera I own is a Pentax MX from approximately 1980, coupled with the exceptional Pentax-M 50mm f/1.7 prime lens. I took this camera rig with me to the Cairngorms in February 2015, loaded up with Ilford XP2 black and white film, and I’m extremely pleased with the images I captured. Film has a uniquely beautiful quality and modern scanning can result in razor-sharp 12MP digital images.

But film isn’t particularly practical. You are severely limited in terms of how many photos you can take, and there is no way of previewing the image you’ve just taken. The equipment is also physically heavy compared to the compact cameras I’ve carried in the past (albeit, in the case of the Pentax MX, significantly lighter than a DSLR rig). For these reasons, the film gear only comes with me very occasionally when I go into the mountains.

Overall the advantages of light weight and compact dimensions are, for me, worth it over lugging a DSLR around

My go-to digital camera of choice is the new Fujifilm X30. This is a mirrorless compact camera with a 2/3-inch sensor – not as big as the Micro 4/3 cameras currently very popular with outdoor professionals, and with a fixed zoom lens, but the image quality is more than good enough for my needs and this camera has a number of features that make it ideal for backpacking.

Firstly, its physical design is robust and easy to hold, made almost entirely of metal with a rubber grip. It weighs a shade over 400g with memory card and lens hood. It can be largely controlled by manipulating its traditional dials – mode and exposure compensation on the top plate, mechanical zoom and control ring on the front. The control ring can be used for highly accurate manual focusing or any of a number of other functions. Full manual control on this camera feels as good as it does on any film rangefinder.

The camera has an excellent electronic viewfinder which is a major step up from trying to frame an image on an LCD screen. It has optical image stabilisation, a critical feature for any mountain camera. And the fast f/2-f/2.8 lens covers a decent zoom range too, from wide angle to telephoto. I also like the 450+ shot battery life and the fact that it can be directly charged through USB, making things considerably easier when it comes to power management on the trail. Built-in wifi makes it easy to transfer photographs to a smartphone for editing and sharing to the Web.

This camera is a major upgrade for me over my previous Canon Powershot A800. It won’t produce images as good as a full-frame DSLR, but in many typical mountain photography situations it would actually be difficult to tell the difference unless you pixel-peep at 100% magnification. It can produce noise-free results at ISO 100 and is capable of creating very sharp images thanks to the excellent fixed lens and vibration reduction. However, its low-light performance is less good than cameras with larger sensors – this is where the laws of physics come into play! Images above ISO 800 tend to be increasingly grainy, for example. And dynamic range won’t be as good as a more expensive camera. I’ve found that shooting in raw can help to overcome these shortcomings, and overall the advantages of light weight and compact dimensions are, for me, worth it over lugging a DSLR around.

Here are the accessories I carry for my camera:

- ThinkTank Mirrorless Mover 5 camera case. This is exactly the right size for my camera and its accessories, it fits on the waist belt of my rucksack, and it has a waterproof rain cover. The best part? It only weighs 146g!

- UV filter. Essential for keeping debris away from the lens in harsh mountain environments. This filter is kept on the lens at all times; I don’t use a lens cap.

- Lens hood. I have a low-profile slotted metal lens hood that can improve contrast and avoid flare in difficult lighting situations.

- Circular polarising filter. Valuable for certain situations in landscape photography.

- Lens cloth. Because condensation will get on your lens.

- Pedco Ultrapod II. This is a new addition to my kit – an ultralight (118g) tripod with ballhead and a sturdy velcro strap for attaching it to all kinds of things.

Power supply

Keeping this lot working is, of course, the key to the system. If you haven’t thought through your power supply strategy then you might as well leave the gear at home for any trip longer than a few days.

For longer trips, especially to remote locations, you will need some way of replenishing your power supply

Nowadays you can buy external USB battery packs that can be recharged and then used to top up devices in the field. These packs have a capacity measured in mAh, commonly ranging from around 2,000mAh (enough to charge most phones once) to 20,000 or more. There are compromises involved at both ends of this scale. The smaller power packs are very light and charge very quickly, but only store a tiny amount of power. They are only suitable for short trips, or (potentially) in combination with a solar panel in areas with bright and abundant sunlight. The very large batteries store a huge amount of power, often enough to charge a phone many times, but are very heavy and can take a very long time to charge (often as long as 24hrs plugged into the mains). The slow charging time is a deal breaker for the average backpacker who rarely stays anywhere for that long.

My favoured solution is a 12,000Ah pack by Powergen. It weighs only 292g with the necessary cables, and stores enough juice to recharge my smartphone 4-5 times. I can fully charge it in about five hours from a 2A mains charger. For most purposes this power bank alone will provide enough energy, and I often won’t take a mains power adapter or solar panel to top it up.

For longer trips, especially to remote locations, you will need some way of replenishing your power supply. If you expect to encounter pubs, campsites or cafes at least once a week, then a 2A compact mains charger is the easiest solution. This is the setup I took on the Cape Wrath Trail; I only had to charge the power supply twice on the whole journey, although I used my phone very sparingly.

In anticipation of more remote trips in the future, I’ve recently invested in a Portapow 7W folding solar panel. This weighs 363g and only cost me £20, but initial tests suggest it’s more than powerful enough to meet my energy demands on the trail, providing it’s exposed to a couple of hours of direct sunlight every day. The idea is to use the panel to keep my power bank topped up. This panel is good enough to trickle charge even in the shade, although I doubt I could use it for long trips in the UK; it’s more suited to the stronger sunlight of hot countries and high altitude. I have experience of using a much smaller solar panel in the UK and it was of very little value.

When I hike the Tour of Monte Rosa in a couple of weeks, I’ll be taking the solar panel and my 12,000Ah power supply. The overall weight is increased, but my power demands will be heavier than on the CWT – I’m taking a better camera, and hope to blog from the trail. The solar panel should pay for itself in terms of versatility.

Keyboard

I can see you scratching your head. A keyboard? In the wilderness?

If you’re using a smartphone for recording or entering a lot of text, you might decide that a folding wireless keyboard is worth the weight. If, for example, you are blogging from the trail or keeping a journal on a smartphone then it’s absolutely worth it. I’ve tried typing longform pieces on a touchscreen keyboard before and it’s no fun – in fact, the experience is so poor that you end up recording far less detail and are far less articulate. A quality keyboard can make the difference between remembering everything about a day on the trail and forgetting it.

Of course, this boils down to the question of whether or not you choose to use an electronic device to store your journal. Historically, I’m split 50/50 on this. I have a number of paper trip journals in which I’ve recorded my adventures by hand, but for many trips I’ve chosen to write my journals electronically instead. There’s something special about writing a journal on paper but, as with everything in this article, there really is no right or wrong way to do it. Many backpackers don’t journal at all and simply use their camera to record their journey.

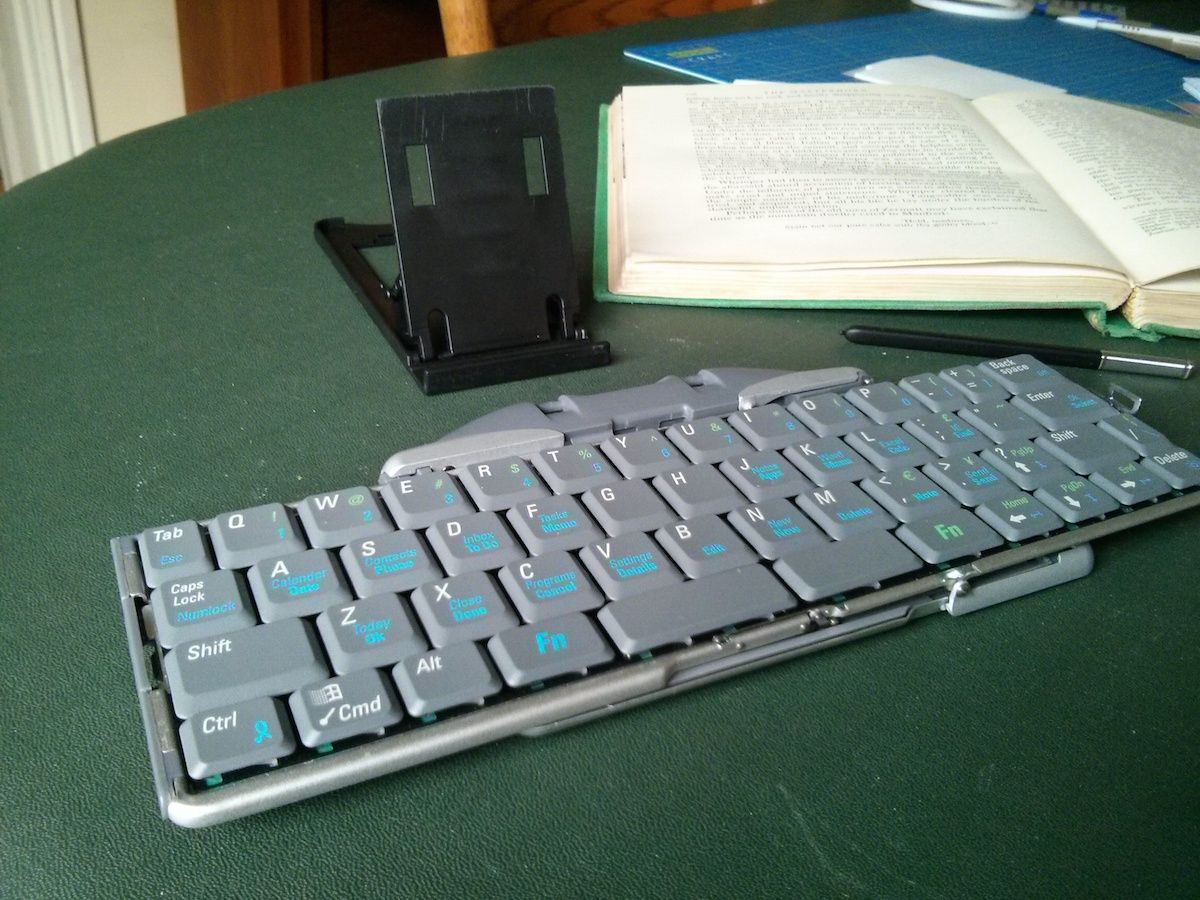

So if you’ve made the decision to carry a keyboard, what do you look for? The primary consideration is weight; this is, after all, very much a luxury item. I would not consider any keyboard weighing more than 200g. It must also be a folding design, as durable as possible – that usually means an aluminium shell. Excellent battery life and a reliable wireless connection are also important. Most Bluetooth portable keyboards can run for months on a single charge. Finally, it must be comfortable to type on, which means quality keys and a non-goofy keyboard layout.

At the moment there are only really two keyboards that fulfil all those requirements. The first is the venerable Think Outside Stowaway Keyboard, which has been around for many years and will connect to anything with a Bluetooth antenna. The typing experience is excellent, it’s lightweight, runs on AAA batteries, and is made from aluminium. The only snags are that a) it lacks dedicated number keys; b) the layout is decidedly goofy; and c) it’s impossible to find new, and often incredibly expensive used.

My keyboard of choice is the EC Technology wireless keyboard. This is essentially an updated version of the Stowaway, but with a slightly different folding design, a built-in rechargeable battery, and dedicated number keys. Its layout is very similar to a regular laptop keyboard and I can type effortlessly on it. At 184g I’m quite happy to carry it into the wild, although as a luxury item it’s one of the first things to be ditched if I’m looking to save pack weight.

I have used one of these keyboards for quite a while and it’s my first choice if I need to keep an electronic journal or blog from the trail.

Conclusion

All the gear I mention above weighs in at a total of 1.8kg. This is a significant chunk of my overall pack weight, but in terms of the value per gram it’s actually hard to beat. This gear allows me to communicate with anyone in the world, capture and share my adventure quickly and easily, navigate more efficiently, carry a library of entertainment material, and supply enough power to do all this without worrying about dead batteries.

Nothing on this list can be said to be essential except for the headtorch, and depending on the objectives of any given trip I may well decide to leave some of the items at home. But it’s a versatile setup and each piece of equipment has been carefully chosen to suit my specific needs. I can pick and choose whatever I require from this arsenal.

I’m interested to hear about the electronic gear you take into the hills. Feel free to grab me on Twitter!

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)